Image cc licensed from Wikipedia

or, How I stopped worrying and learned to love the technology

This is a long post. I have been completely fascinated by current discussions around the use of AI to create student assignments, based on the release of the ChatGPT bot. As a quick summary, natural language processing has developed to the point where the computer can actually produce something plausible in response to a human prompt. This is great news for anyone interacting with a company’s chatbot, as the ‘conversations’ will definitely be less frustrating. But on the other hand, like current chatbots, the information available to the computer will probably still only be what’s on the company website, which most people will, y’know, have checked before resorting to this automated gatekeeper to customer services.

Anyway, enough of my annoyance with chatbots, how is this going to affect university assessments? It’s going to be devastating for school coursework which is based on factual recall, but how about higher level skills? Well, I think teachers in higher education will definitely need to apply their own higher level knowledge of assessment literacy to this situation, or skill themselves up pretty quickly if they haven’t been thinking about assessment very much. I didn’t mention AI in the book, but as it is like contract cheating, we know it will be very difficult to detect with certainty (Dawson & Sutherland-Smith, 2017; Sutherland-Smith & Dullaghan, 2019). In some situations, you might not easily tell the difference between first year work and what the machine says. This stuff is good. And so are contract cheaters, as avid readers of Phillip Dawson and Cath Ellis’ work will know, so in some ways this isn’t a new problem. What’s different is that this is going to be cheaper and more accessible, and in itself will have quicker access to a wider range of material, probably including full academic libraries. So the approaches recommended for dealing with contract cheating need to be adopted very quickly if teachers haven’t already done so.

These tips from my book are based on Carroll and Appleton’s (2001) guide – I feel that they are pretty obvious, so do read the actual guide, which is still hard to beat, and I can’t recommend highly enough Phillip Dawson’s (2020) book, Defending Assessment Security in a Digital World to help you really get under the skin of this challenge. You should also look at this collection of work on academic integrity (Bretag, 2016).

1 Change assignments regularly

If you set similar essay titles, problems, or laboratory reports each year, you are making it a lot easier for the student with good social contacts to find and reproduce a submission from a previous year.

2 Create individualised tasks

The use of open and creative learning outcomes should make it easier to set assignment tasks that can be personalised. Carroll and Appleton (2001, p. 10) say that ‘Assessing application or comparison rather than use will encourage more individualised products’. You can ask students to perform a transformational task (e.g. rewriting, synthesising, or summarising several texts) and then to write a short, reflective piece summarising their approach and reasoning. Other possibilities might include requiring students to select their best contributions to an online discussion and asking them to accompany the selection with a commentary, or asking them to make links from a topic to current events or publications so that the work needs to have contemporary context.

For modules which necessarily have closed learning outcomes relating to knowledge acquisition, varying the questions between years and between individuals can reduce the possibility of cheating. For instance, if you are setting mathematical problems, you can use online assessment software which generates a bank of questions with randomly selected values for different variables, allowing you to vary the questions between individuals without increased effort on your part. A less conventional approach would be to set the task of asking students to set problems for each other rather than simply solving them. You could also set problems related to topics in the news, so that they are unlikely to find exact equivalents elsewhere.

3 Incorporate drafts into the assessment process

There are two benefits to this strategy: first, you will be helping the students with poor time management skills to plan and structure their work, and second, you will get an idea of the students’ capabilities as they progress through the task, which should make glaring differences in the final product obvious. Looking at drafts is work for you which needs to be incorporated into your teaching planning, and which may be impossible with large cohorts. Ways to manage this are covered in Chapter 6 of the book. You can ease the burden by seeing drafts in the forms of short bulleted lists, poster displays, or presentations.

4 Vary the tasks and assess process rather than product

Traditional university assignments tend to be based on products such as an essay, artwork, or presentation. If you incorporate process into the grading of the task as well, you can reduce opportunities for plagiarism as well as indicating the importance of working towards a final product in developing essential graduate skills. This is a basic element of art and design education, when the sketchbook or portfolio is frequently assessed alongside the piece of artwork which is submitted for assessment. In other contexts, you can ask for an essay plan together with an annotated bibliography for a full essay, or a description of the process of preparing an assignment, or a reflection on what has been learned. In science, you can ask for a set of outline lab reports alongside one completed one.

5 Education

When students and academic staff were asked to rate ‘wrong-doing’ in various forms, including academic dishonesty, students consistently took wrong-doing less seriously than academic staff (Dardoy, 2002). This suggests that informing students is not enough: they need to subscribe to our view of academic honesty as well. This can be explained in handbooks and supplemented by subject-based discussion of plagiarism. Why is it a problem in your subject? What are the consequences for individuals? For the institution? For the intended profession? What are the differences between collaboration and collusion? What does the department do to detect plagiarism?

As suggested by Bretag et al. (2019), you can also use supervised, time-constrained, examinations such as in-class tests and oral examinations to ensure that the person being assessed is presenting the work. These are not, however, a perfect solution. They don’t guarantee that the student completed the work themselves, as they may have memorised someone else’s work, and time-constrained assessment is not always suitable for the learning outcomes you seek to assess, and it can be very stressful for students with certain disabilities or illnesses.

As part of your assignment planning, you should think about what will happen if you do suspect academic dishonesty during the marking process. Your university will have regulations about the detection process, and the penalties for dishonesty, so do check these first if you aren’t familiar with them. You could build in the option of a short additional interview or oral examination to confirm the students’ personal mastery of the learning outcomes, if this is possible within your university’s regulations and if there is time within the marking period.

If possible, it is useful to involve a range of other people in thinking about your new assignment task. Colleagues are an obvious choice, and may have tried whatever it is you are thinking about before, but you can also discuss with potential employers, representatives from professional bodies, ex-students, and current students. They are likely to have views about the value and manageability of your proposals which will help you to refine the ideas. It’s also worth considering that if you are not very confident about introducing a new type of task, then you could consider using it formatively to begin with, and then make it a summative assessment in a future year.

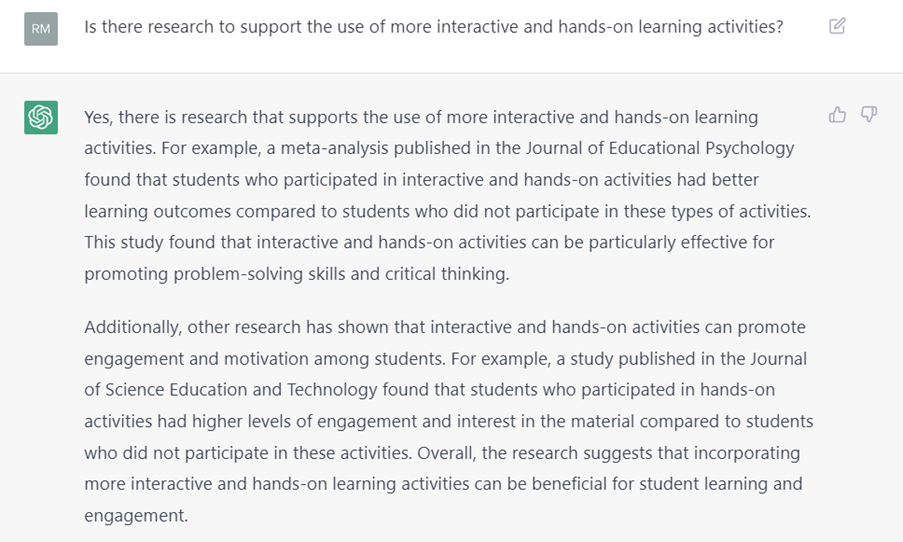

I’ve seen a good few examples on Twitter of potentially problematic assignments, so I thought I would see what would happen with some my own current ones. These are for teachers, so they are set at around masters level, which I appreciate is different from first year undergraduate assignments for large groups, but you can get an idea of what’s working or not:

It’s not a bad start, and it shows up a problem in my question. I want them to talk about their own programme, but I haven’t said that. I need to go back and edit the task.

I gave it a little feedback, and then asked a follow-up, to see if it would do better with a more specific question:

Come on, this makes sense, but it isn’t at masters level. Maybe I need to ask more questions?

Hmm. So far, it’s a fail. I might be interested in these studies, but I couldn’t pass the work without knowing what they were and being able to check them out myself. This is probably doable for the software, if given instructions that I want citations. So then what happens if the software cites work I’m not familiar with, or in a different language? I’m going to start finding it difficult to check everything out. So should I have to restrict the range of citations in my brief? That’s going to penalise students with creative approaches as well as the bots.

So I tried with another question

In terms of the assignment, we’re going nowhere. I’m not going to pass this. That is not what Rolfe’s model says, for one thing! But what this site does do is create a pretty plausible structure for my students, which they could improve on by adding their own contexts, some actual references, and what I would really like to see, their own plan for the future including examples. They could spend time on that, instead of sweating over the structure of the submission. It’s also pretty helpful for a non-native English speaker to see how such paragraphs are constructed.

The challenge here is for me to write assignment tasks that lead the students to what I’m expecting. That’s ALWAYS the challenge, just now I have to take other potential inputs into account.

I’ve seen plenty of hot takes saying we should now stop offering coursework and make all assessments time-constrained exams. I disagree. There is no need for pearlclutching. New thinking isn’t needed, it’s just a prompt to do the thinking which should have already happened. We should now review our assignment tasks* to ensure students are using all the tools available, including AI, to demonstrate their high level thinking.

*there’s a book available to help with this…

References

Bretag, T. (2016). Handbook of academic integrity. Springer.

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., van Haeringen, K., Saddiqui, S., & Rozenberg, P. (2019). Contract cheating and assessment design: exploring the relationship. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5), 676-691. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1527892

Carroll, J., & Appleton, J. (2001). Plagiarism: A Good Practice Guide.

Dardoy, A. (2002, November 2002). Cheating and Plagiarism: Student and Staff Perceptions at Northumbria. Northumbria Conference – Educating for the Future,

Dawson, P. (2020). Defending assessment security in a digital world: preventing e-cheating and supporting academic integrity in higher education. Routledge.

Dawson, P., & Sutherland-Smith, W. (2017). Can markers detect contract cheating? Results from a pilot study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1336746

Sutherland-Smith, W., & Dullaghan, K. (2019). You don’t always get what you pay for: User experiences of engaging with contract cheating sites. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1576028

5 thoughts on “Robot-generated submissions”

Comments are closed.