Image by Sue Thompson on Flickr, (CC BY-ND 2.0).

This blogpost is in response to Neil Currant’s, titled Bin the Assessment Criteria. I’ve used the phrase ‘should we get rid of grades?’ rather than Neil’s use of criteria – I think you would still need criteria for judging the complex ways a task might be considered to be pass/fail, but that could be an ongoing discussion.

I don’t disagree with Neil’s premise. In the UK, and many other countries, higher education has, at least putatively , an outcome-based assessment system. So either you have met the outcome, or you haven’t. This works well for competence-based outcomes and assignment tasks: hand hygiene, or putting up a cannula, or calculating drug dosages, for instance. And Neil is right to say that it can work for complex outcomes, too. And I couldn’t agree more that standards are socially constructed (and thus unreliable between contexts).

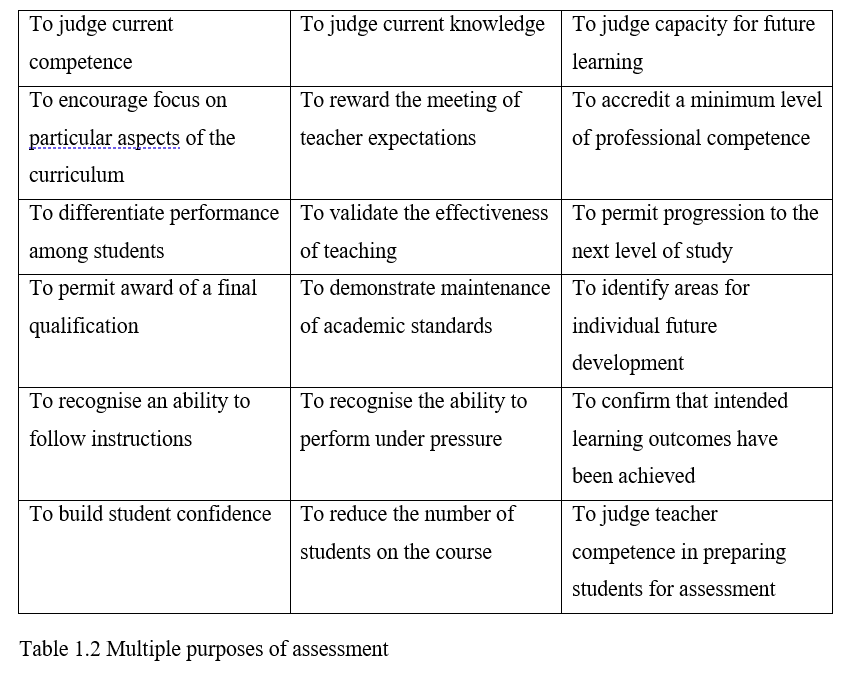

The difficulty comes when assessment is serving more purposes than just assessing learning outcomes. All assessment nerds will be able to quote Boud (2000, p159) saying that assessment always does “double duty” to capture this inherent tension, and to emphasise the need to attend to all potential purposes. In the book, I suggest this list, but I’m sure someone will quickly come up with more:

The trouble is that pass/fail won’t address the one that says “to differentiate performance among students”. I personally agree that this isn’t a necessary requirement of higher education, but not everybody does. I think we’re currently on rough ground with “identify areas for individual future development”, too. Pass/fail on a complex task makes it difficult to provide nuance on strengths and weaknesses. (Yes, feedback could fill that gap, and yes, marking criteria often lack that nuance too).

If we want to differentiate student achievements, then we can do better.I think it is possible to make judgements about the to which a learning outcome has been addressed beyond a pass. Criteria need to use descriptive language which relates to the context of the learning outcome – not ‘good, very good, excellent’ which are words which are difficult for students and graders to interpret. There is quite a lot about how to do this in the book, which I’ll come back to in a future post.

Basically, any conversation about binning the criteria needs to start with ensuring that we are all agreed on the purposes of the task. We would probably get there more quickly if we could somehow get rid of the ridiculous UK classification system, which offends not only by pretending that standards are not socially constructed, but is also a mathematical horrorshow in a modular system.

More reading

Blum, S. D., & Kohn, A. (2020). Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). West Virginia University Press.

Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable Assessment: rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 151–167. http://www.journalsonline.tandf.co.uk/openurl.asp?genre=article&id=1T2QWWDGEF2JPUQ9

Burgess, R. (2007). Beyond the honours degree classification: The Burgess Group final report. UUK. Burgess report 2007

Stommel, J. (2018). How to Ungrade. https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-ungrade/

Thanks Rachel for your post. I look forward to your book coming out. Yes that ‘double duty’ element is a really tricky one. I don’t think there is an easy way out of being able to satisfy all the purposes of assessment that you list. At the moment, the team on the QAA project are mainly trying to challenge deeply held assumptions about assessment and grading and start a conversation. Ultimately for me, I think we need to challenge those multiple purposes and say ‘No that is not the purpose of assessment’ and focus on the main educative purposes.

I was recently listening to Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast. He has two episodes addressing some of the purposes of assessment. He is discussing in the context of Law degrees in the US but I think his logic applies more generally. In Episode 1 (https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/revisionist-history/puzzle-rush) he highlights that the admissions test and subsequent assessments in law school favour a particular way of thinking that might not match up to what is required in the profession. In episode 2 (https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/revisionist-history/the-tortoise-and-the-hare) he talks about how the best law firms only draw from the ‘top’ 14 law schools as a proxy for ‘the best and the brightest’ and concludes that employers should adopt a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy. In others words they should not be allowed to know where graduates went to university and how well they did on university assessments and base hiring decisions of other factors. In other words, assessment should not be used in HE to differentiate performance amongst students because it does not correlate well with performance in the workplace.

LikeLike

thanks, for the comment and the recommendations. We definitely need to have these conversations more loudly. There is no evidence for saying that those ‘top 14’ schools have the highest academic standards (especially as external moderation of academic standards is not usually done in the US, as far as I know). In 2009 the VCs of Oxford and Oxford Brookes univerisities were asked how someone could tell the difference in strandards between their history (I think) degrees, and they couldn’t (or wouldn’t) answer (IUSS, 2009). We need to talk more about academic standards and then the discussion about criteria will improve. For the moment I’m still dumpster diving for the vestiges of their value 🙂

IUSS (2009) Students and Universities. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmdius.htm

LikeLike